9/16- Tuesday –

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal asked readers, do you know your own historical meaning?

How do you learn that? Where you come from? Who do you come from? Where do you fit in history? It is not easy. It is time consuming. It requires patience. It may mean learning new skills and visiting faraway places. Nevertheless the impediments are vastly overwhelmed by the benefits, namely that you can enrich your understanding and experiencing of what is around you. For example…

PROVIDENCE RHODE ISLAND

I visited Providence many years before to participate in an athletic event at Brown University. I had no idea at the time that I had ancestors that were among the very first settlers of Providence. If I did, it would have added much to my visit back then. Now that I do know my ancestors were among the very first settlers of Providence, a visit there is a step back into a distant but personal past.

We parked on S. Main Street near Smith Street. We learned later by overlaying the map of first settler lots on a Google Earth map of Providence that the place we parked coincided with the approximate location of a Scott line ancestor, John Throckmorton’s early home lot.

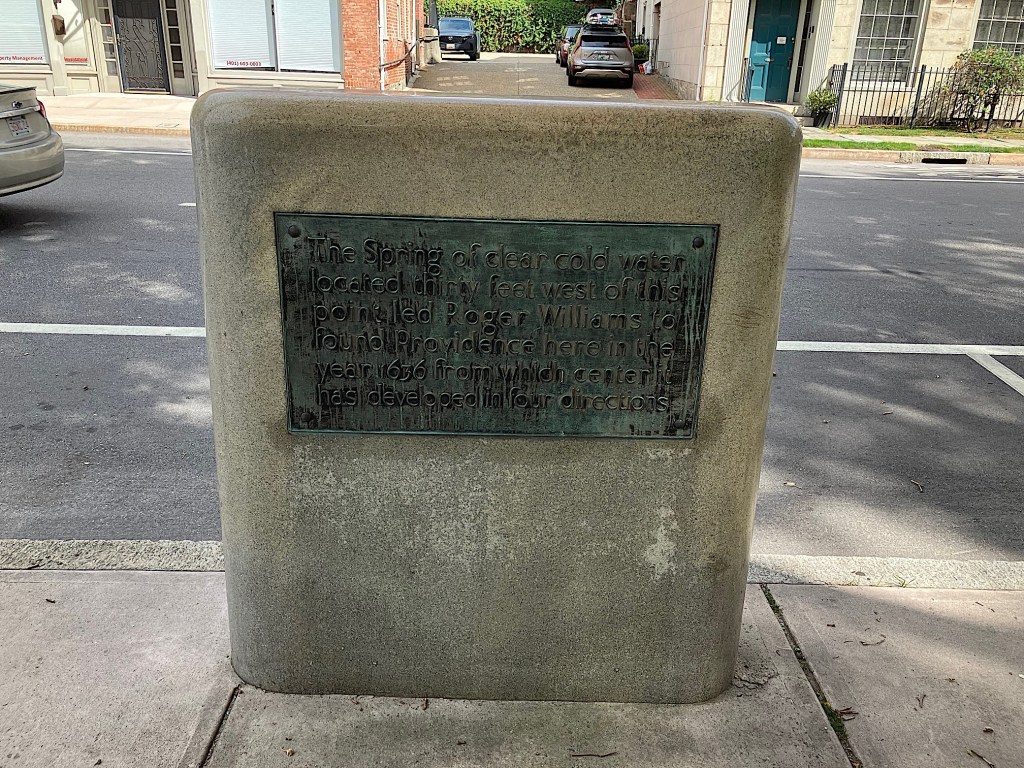

Roger Williams selected the location where he and the first settlers of Providence located in 1636 in part because of close proximity to a spring:

“Roger Williams surveyed the neck of land which he had skirted. A hill rose sharply, east of the spring, to a height of 200 feet. The descent to the east and south was more gradual. Thick forests covered most of the territory, with swamps at the lower levels. A brook flowed southerly through the neck, curving westerly, near its mouth, to discharge into Mile End Cove. Between the bend of the brook and the southerly shore of the neck Foxes Hill rose to a height of about 40 feet. A gravelly beach extended from Fox Point northerly to the mouth of Moshassuck river.

Having determined that the region was well adapted for a settlement Williams negotiated a purchase of land from the Narragansett sachems Canonicus and Miantonomi. Shortly afterwards he and his followers abandoned their former settlement by Ten Mile river, moved over to the spring, and there planted the town of Providence. A clearing was made at the foot of the hillside, near the spring, where dugouts, wigwams or other primitive types of shelter were put up for habitations until the settlers were able to construct more permanent dwellings.

The purchase from the Indians was confirmed in a deed to Roger Williams, executed by the Narragansett sachems, Canonicus and Miantonomi, in March, 1637.” (Emphasis added, internal quotations omitted).[1]

Clearly life was tough at first. Living in a dugout, (hole in a hill), wigwam or primitive shelter is not ideal. These families were desperate exiles, voluntary or not, from towns like Salem that Williams had fled that disagreed with their religious beliefs.

We hoped to visit the National Park visitor center at the Roger Williams National Memorial. The visitor center is said to be built on what was the property of Roger Williams in the early days of the colony. The building has very limited hours and was closed.

Excavation of the site showed that Williams’ house conformed to a plan that was popular among the first colonial settlers. The black outline in the floor plan below was typical of colonial construction. [2]

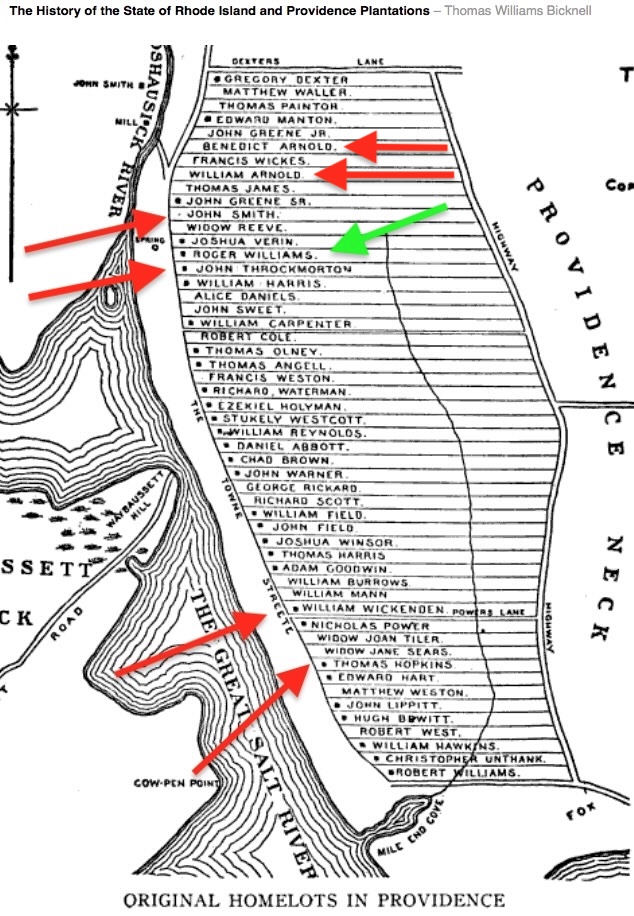

The map below shows lots owned by early settlers 390 years ago. Roger Williams’ lot is next to the spring and is marked by a green arrow. The red arrows mark the lots of our ancestors and our close relations, the Arnolds. John Smith’s lot is the third lot above Roger Williams’ lot and the Arnold’s lots are three and five lots above that. Thomas Hopkins and William Wickenden’s lots are lower down on the map, the 9th and 13th lots above Mile End Cove respectively. Scott family ancestor John Throckmorton’s lot is next to Roger Williams’ lot.

John Throckmorton experience in early America was unique to him but is an example of the unsettled existence of the early settlers. He was a friend of both Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson. Throckmorton and his family sailed to America in 1631 on the ship Lyon with Roger Williams and his wife and settled in Providence next to him.[4] John Throckmorton, also purchased land in 1643 from the Dutch. Now part of the Bronx in New York City, it is called Throg’s Neck.[5] His settlement there was close to where Anne Hutchinson and others of their group were killed by Indians.

John Throckmorton’s (Jan in Dutch) New York Deed

“We, William Kieft, director general, and the council, in behalf of their high mighty lords, the States General of the United Netherlands…do publish and declare that we, on this day under written, have given and granted unto Jan Throckmorton a piece of land…Done in Fort Amsterdam in New Netherlands, this 6th day of July 1643.”

Throckmorton’s settlement was attacked very soon after purchase at the outbreak of Kieft’s War. Throckmorton escaped the attack and moved back to Providence.

“Among the thirty-five associates who accompanied Throckmorton to New Amsterdam were Thomas Cornell and the noted Mrs. Anne Hutchinson. His settlement there, however, was one of short duration, for Winthrop records in Sept. of the same year, 1643, that the Indians set upon the English who dwelt under the Dutch, and killed such of Mr. Throckmorton’s and Mr. Cornell’s families as were at home. Anne Hutchinson and her family were cruelly murdered”. [6]

Throckmorton’s life was filled with danger and uncertainty but he and the other settlers were laying a solid foundation for those yet to come. Thomas Hopkins Sr. (1616-1684), my 9th great-grandfather, was the progenitor of the American family that would produce Esek Hopkins, Commander of the US Navy during the Revolution, and Stephen Hopkins, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a future governor of RI. [7] [8] [9]

On the first settler home lots map six lots above Roger Williams we see William Arnold, uncle to Thomas Hopkins. Two lots up from him we see Benedict Arnold, William Arnold’s son and Thomas Hopkins’ cousin, who was also a future governor of the Rhode Island colony. [10] [11]

We biked along the canal through River Park from Smith Street to Mile End Cove to see what once was the first settlers area. Smith Street is possibly named after John Smith a 10th great-grandfather who lived very near that location. Called “John Smith the Mason” he occupied lot 42.[12] Counting the lots up from Mile End Cove on the map of early settlers lots we see John Smith at lot number 42. Biking from there along Canal Street to Mile End Cove we traced the canal waterfront line of properties.

The ride ended at the Mile End Cove and was shorter than we expected. Other than names on street signs and Roger Williams National Memorial little along the canal remains as a reminder of the first settlers. Providence is steeped in history and historic buildings, but much of it is unmarked. We stopped to take a photo of the street sign at Wickenden Street, named after William Wickenden my 10th great-grandfather and one of America’s first Baptist pastors. [13]

An overlay of the first settler map on top of google earth’s current map of Providence shows the approximate location of the old lots (Mile End Cove at bottom center and Roger Williams’ lot, top left are marked by red dots).

There are many historical homes and buildings uphill from the canal where Roger Williams and the other first settlers resided. These homes and buildings echo the city’s prosperity as it grew from its first settlement to the large city that it is today.

We biked to the Providence Historic Society and then to the John Brown mansion and museum. The mansion was once home to a wealthy Providence family in the 1700’s.[14] The mansion is strongly built and loaded with artifacts from different eras of American history.

Next we biked to the first Baptist Church in America. A beautiful structure in an ancient place with a remarkable history. I am delighted to rescue the memory of the family’s association and contribution to the creation of Rhode Island, the city of Providence, and to the Baptist Church in America. Our next stop was Block Island.

BLOCK ISLAND

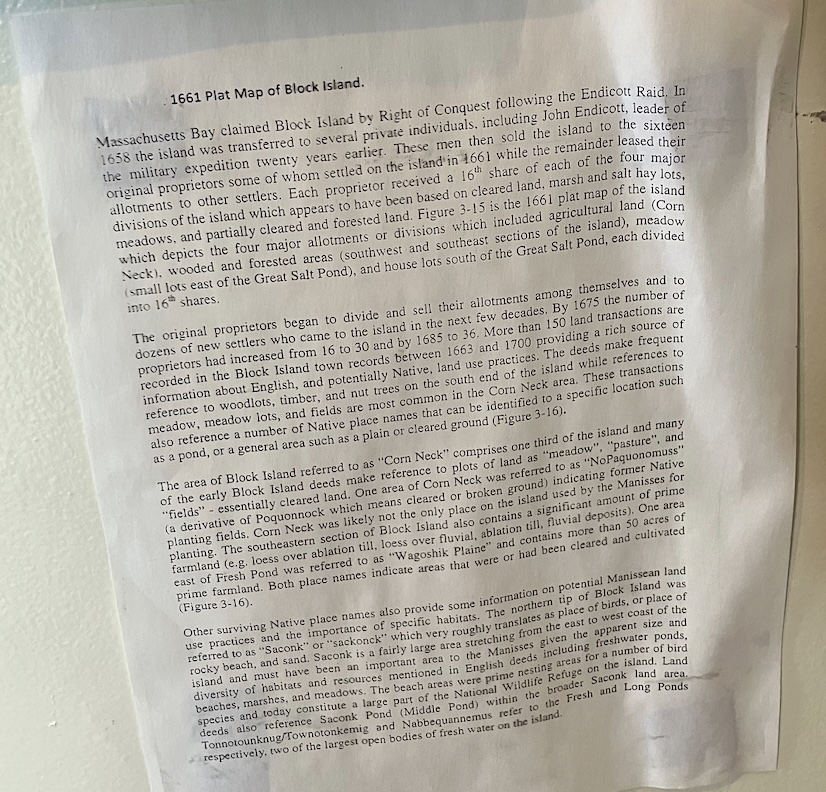

9/17 – Wednesday – Nine miles off the mainland coast, Block Island is accessible by ferry. We took the Point Judith ferry with our bikes to New Shoreham on Block Island, a one hour trip. After arrival we rode bikes to the Block Island Historical Society located in a two story house not far from the ferry landing. The Society had many artifacts, but we saw few from the early colonial days. Most notably for us it had an antique map of the lots owned by the first settlers.

The map appears elsewhere online but what is online is not very legible. We were able to take several photos of the map that enabled us to place the lots once owned by two of my ancestors. The map has an article below it explaining some of the island’s history, (see photo below). Finding the map at the Society was a nice discovery.

A photo of the map of the island appears below. The red arrows point to James Sands’ (1622-1694), properties and the yellow arrows point to Samuel Dearing’s ( -1671) properties. The locations of the properties are given at the bottom of the map, enlarged and highlighted, below.

The island was sold in 1660, to be split among about 16 families for 400 pounds:

“Mr. John Alcock acquainting them of an island that was to be sold, namely, Block Island, which might make a situation for about sixteen families, and also declaring the price to be four hundred pounds…” [16]

After we took photos of the map the docent at the Society directed us to the north end of the island, a spot called Sandy Point. There, we located the monument that marks where the settlers first landed.

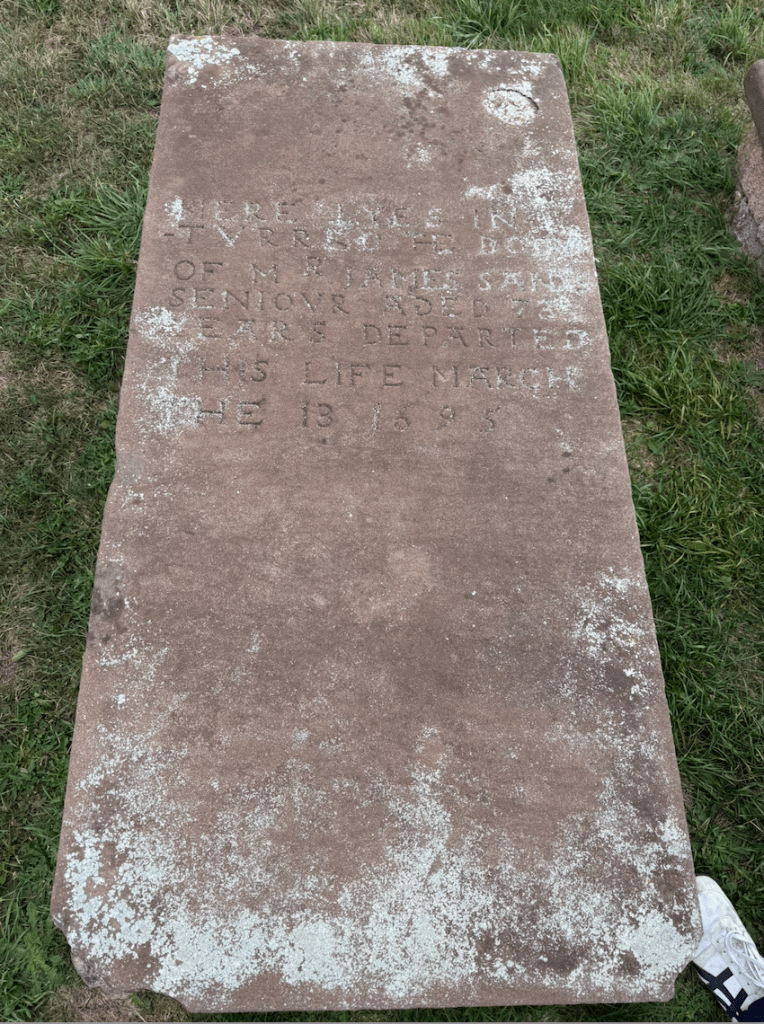

The marker lists the names of the Island’s first settlers. On the marker James Sands, my 10th great-grandfather, is noted as an original purchaser of a portion of the island. Reading the names on marker showed another name I was familiar with and I investigated further to see if this was same man as the man that appeared in my family tree.

Samuel Dearing, my 8th great-grandfather is noted on the marker as a first settler and as an original purchaser.[18] He and his in-laws both owned Block Island lots.[19]

Until I started writing this article I was unaware that Samuel Dearing was a Block Island purchaser and settler. One of his great-grandsons, Deering Jones Jr., was at the battle of Lexington April 19, 1775. Deering Jones Jr., is one of my Revolutionary War ancestors as validated by the genealogists at the Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

Samuel Dearing relocated to Braintree Massachusetts after living a few years on the island. James Sands lived out his life on the island.

It is fascinating to visit the places where your earliest American ancestors lived over 350 years ago. We sat on a nearby driftwood log and we were both struck by the feeling of peacefulness we got while observing the incoming waves.

We rode our bikes from Sandy Point to Old Cemetery. At the Old Cemetery we located the raised slab table type marker for James Sands next to his son Edward Sands. After paying our respects and taking photos of the marker we headed back to the port. It started raining lightly so we rode to a restaurant near the ferry and waited out the rain for ½ hour, then got on the ferry.

Block Island has kept much of the modern world from encroaching. Fieldstone fences, limited development, some old farms along narrow roads, help to transport visitors back to earlier times. Discovering more about how the family intertwined with early American Rhode Island and Block Island strengthens our understanding of our family’s historical meaning and impact, and I am sure there is more to discover.

A photo of the 1661 map transposed over a Google Earth map of the island appears below.

[1] John Hutchins Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of the City of Providence, p. 4, The Bookshop, Providence, 1957. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/civicarchitectur00cady/civicarchitectur00cady.pdf

[2] John Hutchins Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of the City of Providence, p. 9, The Bookshop, Providence, 1957. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/civicarchitectur00cady/civicarchitectur00cady.pdf

[3] John Hutchins Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of the City of Providence, p. 10, The Bookshop, Providence, 1957. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/civicarchitectur00cady/civicarchitectur00cady.pdf

[4] Charles Edward Banks, The Planters of the Commonwealth; A Study of the Emigrants and Emigration In Colonial Times: To Which are Added Lists Of Passengers to Boston and to the Bay Colony; The Ships Which Brought Them; Their English Homes, and the Places of Their Settlement In Massachusetts. 1620-1640, p.92-93, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1930. https://archive.org/details/plantersofcommon00bank/page/92/mode/1up?q=%22roger+williams%22

[5] Frances Grimes Sitherwood, Throckmorton Family History, p. 47, Bloomington, Illinois, Pantagraph Printing, 1929. https://archive.org/details/throckmortonfami00sith/page/n115/mode/1up

[6] Frances Grimes Sitherwood, Throckmorton Family History, p. 48, Bloomington, Illinois, Pantagraph Printing, 1929. https://archive.org/details/throckmortonfami00sith/page/48/mode/1up

[7] Thomas Hopkins, Settler, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hopkins_(settler)

[8] Esek Hopkins, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esek_Hopkins

[9] Stephen Hopkins, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Hopkins_(politician)

[10] Benedict Arnold, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_Arnold_(governor)

[11] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration Begins, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2496/records/14514?tid=&pid=&queryId=375749cc-ec0a-4cd8-aaf0-c314e8787650&_phsrc=Lvd80&_phstart=successSource

[12] John O. Austin, The Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island, p. 380, Munsells, Albany, 1887. https://archive.org/details/genealogicaldict00aust/page/380/mode/1up?view=theater

[13] Henry Melville King, Compiler, Ed., Historical Catalogue of the Members of the First Baptist Church in Providence Rhode Island, p. 23, Townsend, Providence R.I., 1908. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MylOAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA22&hl=en

[14] John Hutchins Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of the City of Providence, p. 63-65, The Bookshop, Providence, 1957. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/civicarchitectur00cady/civicarchitectur00cady.pdf

[15] Charles Wyman Hopkins, The Home Lots of the Early Settlers of the Providence Plantations, p.18-19, Providence Press, Providence, 1886. https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/viewer/572707/?offset=0#page=29&viewer=picture&o=info&n=0&q=

[16] Rev. S. T. Livermore, A. M., History of Block Island, p. 14, Case Lockwood & Brainard, Hartford, 1877. https://archive.org/details/historyofblockis00live/page/14/mode/1up

[17] Rev. S. T. Livermore, A. M,. History of Block Island, p. 270, Case Lockwood & Brainard, Hartford, 1877. https://archive.org/details/historyofblockis00live/page/270/mode/1up?

[18] Rev. S. T. Livermore, A. M,. History of Block Island, p. 14-19, Case Lockwood & Brainard, Hartford, 1877. https://archive.org/details/historyofblockis00live/page/14/mode/1up

[19] Walter Goodwin Davis, Massachusetts and Maine Families in the Ancestry of Walter Goodwin Davis. Vol. I, p. 418, Genealogical Pub. Co., Baltimore, 1996. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/48192/images/MAMEFamiliesI-002730-418?pId=235243

Copyright Bruce Wright, Esq. 2025 ©