In 1689 only eleven years after the end of King Philip’s War the French and Indians began a rampage in New York and New England that would be called King William’s War. The year 1690 saw the rampage continue when Schenectady New York was attacked and burned in February. In March 1690 the settlement at Salmon Falls Maine was attacked and decimated. In May 1690 Casco Maine was destroyed and Fort Casco taken.[1] Hundreds of settlers were killed in these attacks and many were captured.

Noah Wiswall lived at the southern shore of what was then named Wiswall’s Pond and today is known as Crystal Lake in Newton Massachusetts.[2] [3] He and his wife Theodosia married in 1664. She was the daughter of John Jackson, the first recorded settler of Newton, who settled there in 1639.[4]

Noah’s father Thomas Wiswall was also an early settler of Newton. Thomas bought his property by the pond, now called Crystal Lake, in 1654. “Thomas Wiswall, who purchased 300 acres of the Haynes land holdings and who was the first actual settler on the property. Wiswall built his house in 1654 on the Dedham Trail, which is now known as Centre Street, on the south side of the lake near present-day Paul Street… Wiswall died in 1683. For many years, his was the only house in the immediate area, and the pond next to it became known as Wiswall’s Pond.” [5] [6]

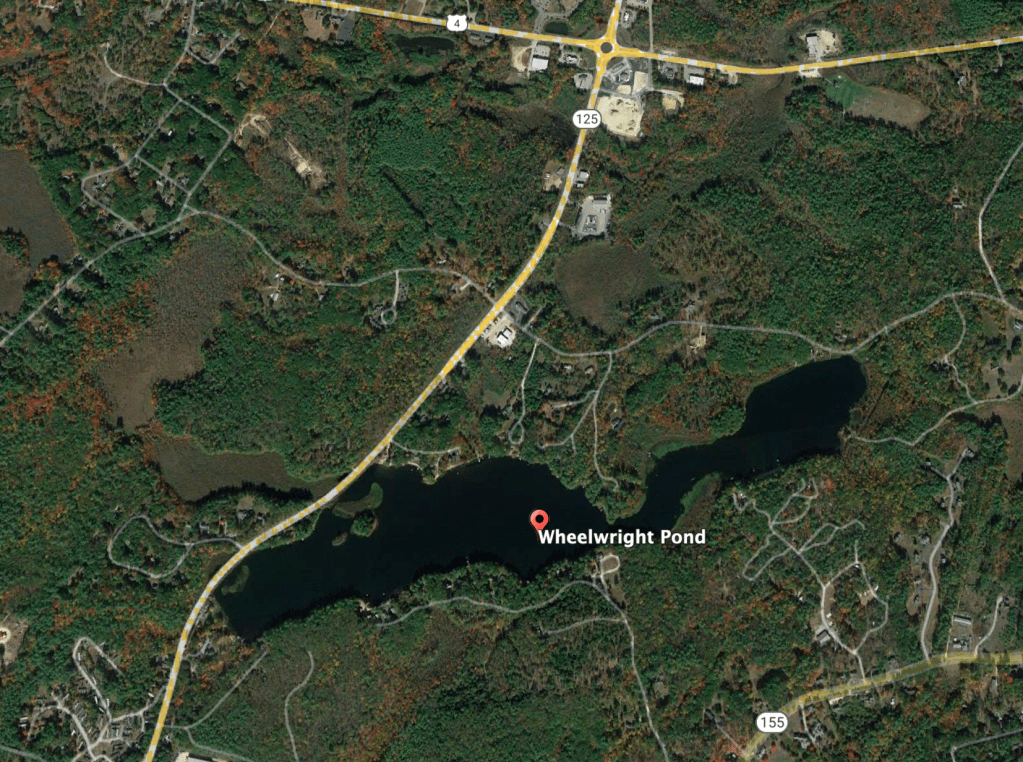

The Battle at Wheelwright’s Pond – King William’s War 1688-1698

It was early July 1690 when Noah Wiswall, my 9th great-grandfather, was called on again to fight the French and Indians. It was into the maelstrom of King William’s War savagery and destruction which he was pulled. He was the father of 10 children. In 1690 Noah was about 50 and his wife was 47 years old. Their children ranged in age from the eldest at 22 years old to the youngest aged 14.[7] Their children would be left fatherless on July 6th. Several historical accounts tell of what happened on that hot July day.

“History gives but few details of the battle at Wheelwright’s Pond, which was a running fight through woods, after Indian fashion, beginning, as local tradition says, at Turtle Pond in Lee and extending to the southeast side of Wheelwright’s Pond in the same town. One hundred men, under command of Capt. Noah Wiswall and Capt. John Floyd, set out from Dover. The fight was on Sunday. Captain Wiswall, Lieut. Flag, Serg. Walker, and twelve privates were killed, when both parties withdrew from the conflict.” [8]

A contemporaneous account comes to us from a man who lived during this time. “Rev. Samuel Niles, was born, as he himself states in this work, on Block Island, May 1, 1674, and was graduated at Harvard College in 1699. He was settled at Braintree May 23, 1711, and died May 1, 1762, aged 88 years.”[9] As an interesting note, Rev. Niles is my first cousin 10x removed.

Reverend Samuel Niles tells us that in 1690,

“On the 4th of July, a Court was called at Portsmouth, in New Hampshire government, and it was agreed to send Captain Wiswel, with a considerable scout, to scour the woods as far as Casco, and determined to send with him one of the other captains, with fourscore stout and able men. There being several captains, they were stirred up with such emulation, that every one of them seemed ambitious of the service, so that they cast lots to determine which of them should go with Captain Wiswel; and the lot fell on Captain Floyd, and that Lieutenant Davis should take a detachment of 22 men from Wells. They took their march from Quochecho, into the woods… July 6, Captain Wiswel and Captain Floyd sent their scouts early in the morning, to see whether they could discover any track of the enemy. They soon returned with tidings of a large track they had found leading westward. The forces vigorously pursued them, and overtook them at a place called Wheelwright’s Pond; and there ensued a bloody engagement, wherein Captain Wiswel, and his Lieutenant, Flagg, and Sergeant Walker, were slain, and 15 of our men also were slain, and more wounded. Captain Floyd continued the fight for several hours, until his tired and wounded men drew off, and he not long after. Of the wounded there died about a dozen. Captain Convers came with 20 men to bury the dead, and found seven men alive among them; these he brought early in the morning to the hospital. It is uncertain whether any of them died of their wounds afterwards or not.” [10]

Reverend Cotton Mather, another famous New England theologian contemporaneous with the times, also tells us the story,

“ON July 6. Lords Day, Captain Floyd, and Captain Wiswell, sent out their Scouts, before their Breakfast, who immediately returned, with Tidings of Breakfast enough provided for those, who had their Stomach sharp set for Fighting: Tidings of a considerable Track of the Enemy, going to the Westward. Our Forces vigorously followed the Track, till they came up with the Enemy, at a place call’d Wheelrights Pond; where they Engaged ’em in a Bloody Action for several Hours. The manner of the Fight here, was as it is at all times, with Indians; namely what your Artists at Fighting do call, A la disbandad: And here, the Worthy Captain Wiswel, a man worthy to have been Shot (if he must have been Shot,) with no Gun inferior to that at Florence, the Barrel whereof is all pure Gold, behaving himself with much Bravery, Sold his Life, as dear as he could; and his Lieutenant Flag, and Sergeant Walker, who were Valiant in their Lives, in their Death were not divided. Fifteen of ours were Slain, and more Wounded; but how many of the Enemy, ’twas not exactly known, because of a singular care used by them in all their Battels, to carry off their Dead, tho’ they were forced now to Leave a good Number of them on the Spot. Captain Floyd maintained the Fight, after the Death of Captain Wiswal, several Hours, until so many of his Tired and Wounded men Drew off, that it was Time for him to Draw off also; for which he was blamed perhaps, by some that would not have continued at it so long as he. Hereupon Captain Convers repaired, with about a score Hands to look after the Wounded men, and finding seven yet Alive, he brought ’em to the Hospital, by Sunrise the next morning. He then Returned with more Hands, to Bury the Dead, which was done immediately; and Plunder left by the Enemy at their going off, was then also taken by them.” [11]

The story of the battle is told in The History of New England published in London in 1720 that states:

“They marched out of Quochecho on the 4th of July, with above 100 Men, and on the 6th came up with a large Party of the Enemy at Wheelwright-Pond. It was observed, that there were several French Soldiers mix’d with these Indians, to discipline and instruct them in a regular Way of Fighting. The Engagement lasted several Hours, but Victory declared at last for the Enemy, Captain Wiswel, Lieutenant Flag, Serjeant Walker, with fifteen of their Men being killed, and a great many more wounded. When Wiswel fell, Captain Floyd retreated with the Remainder of the Army, in the best Manner he could, leaving his wounded Men behind him; but next Morning Captain Convers, with twenty Men, being sent out towards the Place of Battle, found seven of the wounded English yet alive, and brought them back to the Camp.” [12]

Hostilities in King William’s War ended in 1698. Noah Wiswall died early in the conflict. His contribution to the fight was his life and he and the battle that he died in are memorialized in numerous histories. He is remembered once again in this story, written by a descendant 333 years later.

[1] Bruce A. Wright, Esq., Discover Your Roots! Rediscovering the Heroes of the Indian Wars of New England and New Netherlands 1636-1698, p.86-87, by the author, 2020.

[2] Francis Jackson, A History of The Early Settlement of Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts, from 1639-1800, p. 454, Stacy and Richardson, Boston, 1854. https://archive.org/details/historyofearlyse00injack/page/454/mode/1up?view=theater

[3] Srdjan S. Nedeljkovic, Crystal Lake Task Force, Crystal Lake: A Brief History, 2009. http://www.crystallakeconservancy.org/crystal-lake-a-brief-history.html

[4]Francis Jackson, A History of The Early Settlement of Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts, from 1639-1800, p326-327, Stacy and Richardson, Boston, 1854. https://archive.org/details/historyofearlyse00jack/page/326/mode/2up

[5] Srdjan S. Nedeljkovic, Crystal Lake Task Force, Crystal Lake: A Brief History, 2009. http://www.crystallakeconservancy.org/crystal-lake-a-brief-history.html

[6] Francis Jackson, A History of The Early Settlement of Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts, from 1639-1800, p. 452, Stacy and Richardson, Boston, 1854. https://archive.org/details/historyofearlyse00injack/page/452/mode/1up?view=theater

[7] Francis Jackson, A History of The Early Settlement of Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts, from 1639-1800, P. 454, Stacy and Richardson, Boston, 1854. https://archive.org/details/historyofearlyse00injack/page/454/mode/1up?view=theater

[8] Everett S. Stackpole and Lucien Thompson, History of the Town of Durham, p.88, Rumford, Concord N.H., 1913. https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofd00stac/page/88/mode/2up?view=theater

[9] Rev. Samuel Niles, A Summary Historical Narrative of the Wars in New-England with the French and Indians, in the Several Parts of the Country, in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. 6, Series 3, p. 154, American Stationers, Boston, 1837. https://archive.org/details/collectionsofmas36mass/page/154/mode/1up?view=theater

[10] Rev. Samuel Niles, A Summary Historical Narrative of the Wars in New-England with the French and Indians, in the Several Parts of the Country, in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. 6, Series 3, p. 218, p. 224, American Stationers, Boston, 1837. https://archive.org/details/collectionsofmas36mass/page/218/mode/1up?view=theaterhttps://archive.org/details/collectionsofmas36mass/page/224/mode/1up?view=theater

[11] Cotton Mather, Decennium Luctuosum. An history of remarkable occurrences, in the long war, which New-England hath had with the Indian savages, from the year, 1688. To the year 1698, p. 73-74, Green and Allen, Boston, 1699. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=evans;idno=N00725.0001.001;rgn=div2;view=text;cc=evans;node=N00725.0001.001:4.6

[12] Daniel Neal, The History of New-England : containing an impartial account of the civil and ecclesiastical affairs of the country, to the year of Our Lord, 1700, 2nd ed., v.2, p. 95-96, Ward et al., London 1747. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000020049911&view=1up&seq=10

Bruce A. Wright, Esq. © 2024