The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same. Really?

This section of the blog is Part One of a Three Part episode that will talk about family members in early New England that were affected by the miscarriage of justice known as the New England Witch Hunts. Two of those family members figure prominently in witchcraft examples detailed in a book written by the famous early New England minister Cotton Mather. The third family member I discuss was one of those accused at the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

Following the historical trail of the witch hunts in New England in the late 1600’s as they affected three ancestors it becomes clear that people are easily swayed to believe incredulous things. When illogical hysteria infects a whole society and injures an ancestor the story devolves from academically interesting to personally painful. The recognition of the impact to an ancestor, from whom I descend, of being outcast, imprisoned, and punished by countrymen that are idiots and knaves for imaginary things that defy belief is not a good feeling. I am interested in the evidence presented and the rules used in these trials, and I include some of that in this blog.

The whole truth and nothing but the truth. We know that accusations in a court of law need to be supported by real evidence. Repeating what someone else said that they heard someone say about what someone said about what they think or what they saw is not evidence. Inexplicable courtroom histrionics displayed by courtroom spectators or participants is not evidence. Creatures and events spewed from fertile imaginations are not evidence. Unbelievable accusations are just that, not to be believed. However, these things were accepted practice at the time of the New England witch hunts.

Proper rules of evidence were suspended in the New England witch trials. Reason was suspended. Accused of witchcraft? You are guilty until proven innocent. You say no, you did not ride on a stick with others above the trees to a secret meeting in the woods? But it was sworn under oath against you – so it must be true. Never mind that the witnesses against you bear you ill will, are envious of you, harbor a grudge or would profit from your demise.

Over a decade before the insanity of the Salem Witch Trials Mrs. Elizabeth Morse, “Goody Morse” in the lexicon of the time, was accused of being a witch and sentenced to death.[1] Her husband William Morse was a shoemaker who migrated to the New World in 1635 at the age of 21, settled in Newbury MA. Elizabeth and William married there by 1640. In 1679 when “Goodman” William Morse was 65 years old, and their grandson who was no older than 10 years old lived with them, the Morse house occupants experienced a series of events thought to be supernatural.

Modern accounts say that Goodman Morse’s tools would suddenly disappear, while quietly at work at his bench; brickbats and old shoes would come clattering down the chimney without the aid of human hands. These inflictions, often repeated, drove Goodman Morse nearly frantic. To a certainty, the house was bewitched.[2]

According to Morse’s contemporaneous court testimony,

“Last Thursday night my wife & I being in bed, we heard a great noise against the roof with sticks and stones throwing against the house with great violence, whereupon I myself arose, and my wife, and saw not anybody, but were forced to return into the house again, the sticks and stones being thrown so violently against us. We locked the door again fast and about midnight we heard a great noise of a hog in the house, and I arose and found a door being shut. I opened the door again and the hog runneth violently out.”[3]

Morse was convinced by a transient mariner named Caleb Powell that his supernatural ills could be alleviated through his intervention. Powell’s intervention succeeded.

“A mate of a ship came often to me and said he much grieved for me, and said the boy was the case of all my trouble, and my wife was much roughed, and was no witch; and if I would let him have the boy but one day he would warrant me no more trouble. I being persuaded to it, he came the next day at the break of day and the boy was with him until night, and I not any trouble since.”[4]

Caleb Powell was certain the Morse’s grandson was to blame. Unfortunately, Caleb Powell’s intervention was seen by the town as the contrivance of a wizard. The boatswain of Powell’s boat was even said to have called him a wizard so it must be true. Right? Accordingly, Powell was tried as a wizard. Hearsay evidence at his trial was provided by two witnesses:

At the March term of the court at Ipswich (1680) Powell’s case again came up and additional testimony was brought out. “Sarah Hale and Joseph Mirick testify that Joseph Moores hath often said in their hearing that if there were any wizards he was sure Caleb Powell was one.”[5]

The root of the Morse’s supernatural troubles seemingly becomes obvious with the following testimony.

Mary Tucker, aged about twenty, made the following deposition:

“She remerabereth that Caleb Powell came into their house and sayd to this purpose that he coming to William Morse, his house, and the old man being at prayer he thought not fit to go in, but looked in at the window and he sayd he had broken the inchantnient for he saw the boy play tricks while he was at prayer, and mentioned some: and among the rest that he saw him to fling the shoo at the old man’s head.” [6]

Reason somewhat prevailed and Powell was freed, but he was released under a cloud of aspersion.

“Upon hearing the complaint brought to this court against Caleb Powell for suspicion of working by the devill to the molesting of the family of William Morse of Newbury, though this court cannot find any evident ground of proceeding farther against the sayd Powell yett we determine that he hath given such ground of suspicion of his so dealing that we cannot so acquit him but that he justly deserves to beare his owne shame and the costs of prosecution of the complaint.” [7]

All reason was then abandoned and Elizabeth Morse was tried and convicted of being the culprit in the supernatural attacks on her own house and husband. “She was Condemned to death at Boston on 26 May 1680.” [8]

Cotton Mather was a leading New England churchman of the time. In his book Magnalia Christi Americana he includes many delusional examples of witchcraft including two that involve two of my ancestors. In the third witchcraft example in his book he tells the story of Elizabeth Morse:

In the year 1679 the house of William Morse, at Newberry, was infested with dæmons after a most horrid manner, not altogether unlike the dæmons of Tedworth. It would fill many pages to relate all the infestations; but the chief of ’em were such as these:

Bricks, and sticks, and stones, were often by some invisible hand thrown at the house, and so were many pieces of wood: a cat was thrown at the woman of the house, and a long staff danc’d up and down in the chimney; and afterwards the same long staff was hang’d by a line, and swung to and fro; and when two persons laid it on the fire to burn it, it was as much as they were able to do with their joint strength to hold it there. An iron crook was violently by an invisible hand hurl’d about; and a chair flew about the room until at last it litt upon the table, where the meat stood ready to be eaten, and had spoil’d all, if the people had not with much ado saved a little. A chest was by an invisible hand carry’d from one place to another, and the doors barricado’d, and the keys of the family taken, some of them from the bunch where they were ty’d, and the rest flying about with a loud noise of their knocking against one another. For one while the folks of the house could not sup quietly, but ashes would be thrown into their suppers, and on their heads, and their cloaths; and the shooes of the man being left below, one of them was fill’d with ashes and coals, and thrown up after him. When they were a-bed, a stone weighing about three pounds was divers times thrown upon them. A box and a board was likewise thrown upon them; and a bag of hops being taken out of a chest, they were by the invisible hand beaten therewith, till some of the hops were scatter’d on the floor, where the bag was then laid and left. The man was often struck by that hand with several instruments; and the same hand cast their good things into the fire: yea, while the man was at prayer with his household, a beesom gave him a blow on his head behind, and fell down before his face. When they were winnowing their barley, dirt was thrown at them; and assaying to fill their half bushel with corn, the foul corn would be thrown in with the clean, so irresistibly, that they were forc’d thereby to give over what they were about.

While the man was writing his inkhorn was by the invisible hand snatch’d from him and being able no where to find it he saw it at length out of the air down by the fire. A shooe was laid upon his shoulder when he would have catch’d it it was rapt from him it was then clapt’d upon his head and there he held it so fast that the unseen fury pull’d him with it backward on the floor. He had his cap torn off his head and in the night he was pull’d by the hair and pinch’d and scratch’d and invisible hand prick’d him with some of his awls and with needles and blows that fetched blood were sometimes given him. Frozen clods of cow dung were often thrown at the man and his wife going to the cows, they could by no means preserve the vessels of milk from like annoyances which made it fit only for the hogs.

She going down into the cellar, the trap-door was immediately by an invisible hand shut upon her, and a table brought, and laid upon the door, which kept her there till the man remov’d it. When he was writing another time, a dish went and leapt into a pail, and cast water on the man, and on all the concerns before him, so as to defeat what he was then upon. His cap jump’d off his head, and on again; and the pot lid went off the pot into the kettle, then over the fire together.

A little boy belonging to the family was a principal sufferer in these for he was flung about at such a rate that they fear’d his brains would have been beaten out nor did they find it possible to hold.His bed cloathes would be pull’d from him his bed shaken and his staff leap forward and backward. The man took him to keep him in chair but the chair fell a dancing and both of them were very near thrown into the fire.

These, and a thousand such vexations befalling the boy at home, they carry’d him to live abroad at a doctor’s. There he was quiet; but returning home, he suddenly cry’d out, “he was prick’d on the back; where they found strangely sticking a three-tin’d fork, which belong’d unto the doctor, and had been seen at his house after the boy’s departure. Afterwards his troublers found him out at the doctor’s also; where, crying out again he was prick’d on the back, they found an iron spindle stuck into him; and on the like out cry again, they found pins in a paper stuck into him; and once more, a long iron, a bowl of a spoon, and a piece of a pan shred, in like sort stuck upon him. He was taken out of his bed, and thrown under it; and all the knives belonging to the house were one after another stuck into his back, which the spectators pull’d out: only one of them seem’d unto the spectators to come out of his mouth. The poor boy was divers times thrown into the fire, and preserv’d from scorching there with much ado. For a long while he bark’d like a dog, and then he clocqu’d like an hen; and could not speak rationally. His tongue would be pull’d out of his mouth; but when he could recover it so far as to speak, he complain’d that a man call’d P–l, appeared unto him as the cause of all.

Once in the day-time he was transported where none could find him, till at last they found him creeping on one side, and sadly dumb and lame. When he was able to express himself, he said, ” that P–l had carried him over the top of the house, and hurled him against a cart-wheel in the barn; and accordingly they found some remainders of the thresh’d barley, which was on the barn floor, hanging about his garments.

The spectre would make all his meat, when he was going to eat, fly out of his mouth; and instead thereof, make him fall to eating of his ashes, and sticks and yarn. The man and his wife, taking the boy to bed with them, a chamber pot with its contents was thrown upon them; they were severly pinch’d and pull’d out of bed; and many other fruits of devilish spite were they dogg’d withal, until it pleased God mercifuly to shorten the chain of the devil. But before the devil was chain’d up the invisible hand. which did all these things, began to put on an astonishing visibility.

They often thought they felt the hand that scratch’d them, while yet they saw it not; but when they thought they had hold of it, it would give them the slip. Once the fist beating the man, was discernible, but they could not catch hold of it. At length an apparition of a Blackamoor child shew’d itself plainly to them. And another time a drumming on the boards was heard, which was follow’d with a voice that sang, “Revenge! revenge! sweet is revenge!” At this the people, being terrify’d , call’d upon God: whereupon there follow’d a mournful note, several times uttering these expressions :”Alas! alas! we knock no more, we knock no more!” and there was an end of all.[9]

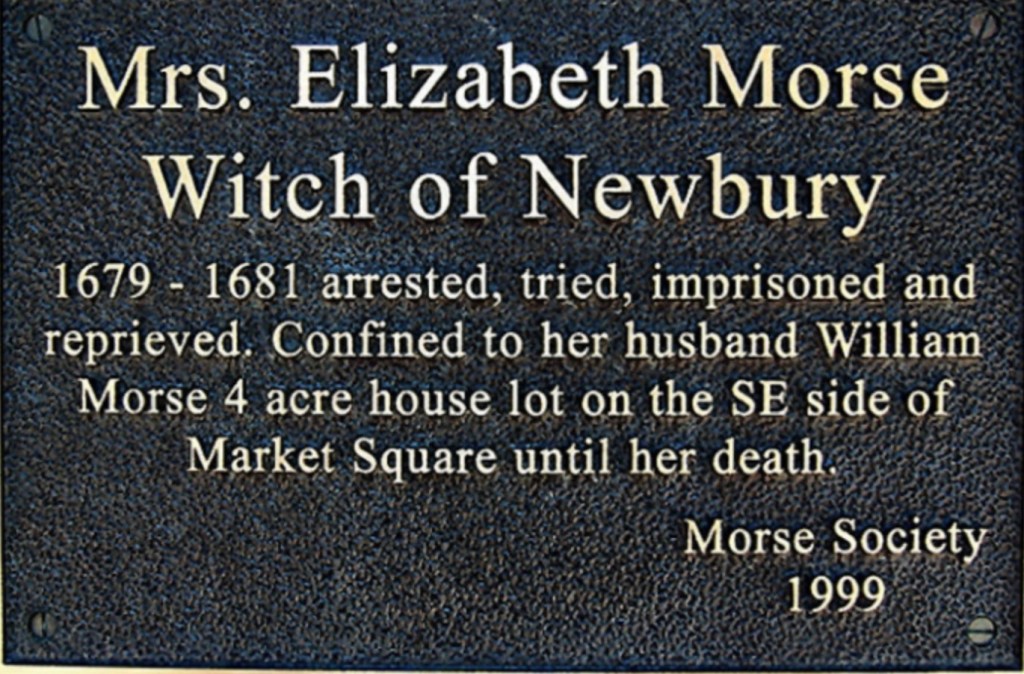

That is a rendition of the events at the Morse house as related by a prominent minister of the time. Such was the lunacy that prevailed in Newbury Massachusetts around 1680. Elizabeth Morse did not escape the lunacy unscathed. Initially condemned to death she “languished in jail for over a year, then was allowed to go home.” She died a natural death after August 1683.[10] She was reprieved but released only to endure the remainder of her life under house arrest. Her life after the witchcraft accusation is briefly summarized on a plaque erected to her memory by some of her descendants.[11]

[1] Historic Newbury, The Witchcraft trial of Elizabeth Morse of Newbury, 1680. https://historicipswich.net/2021/06/06/the-witchcraft-trial-of-elizabeth-morse-of-newbury/ Last accessed June 26, 2023.

[2] Samuel Adams Drake, A Book of New England Legends and Folk Lore in Prose and Poetry, p. 315-316, Boston, Little, Brown and Co., 1901. https://archive.org/details/bookofnewengland00dra/page/314/mode/2up Last accessed June 16, 2023.

[3] Id. at 316.

[4] Id.

[5] Id. at p.316-317.

[6] Id. at p. 317

[7] Id.

[8] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration, v. 5, pgs. 178, 180. Boston, New England Historical and Genealogical Society, 1996-2011.

[9] Cotton Mather, D.D. F. R. S., Magnalia Christi Americana; Or, The Ecclesiastical History of New England, v. 2, p. 450-452, London, 1702. Reprint Silus Andrus and Son, Hartford, 1853. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/iCxKAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1 Last accessed June 16, 2023.

[10] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration, v. 5, pgs. 178, 180. Boston, New England Historical and Genealogical Society, 1996-2011.

[11] Historic Ipswich, The Witchcraft Trial of Elizabeth Morse of Newbury, 1680, https://historicipswich.net/2021/06/06/the-witchcraft-trial-of-elizabeth-morse-of-newbury/ Last accessed June 16, 2023.